Policy is Hard

ft. Arrow's Impossibility Theorem

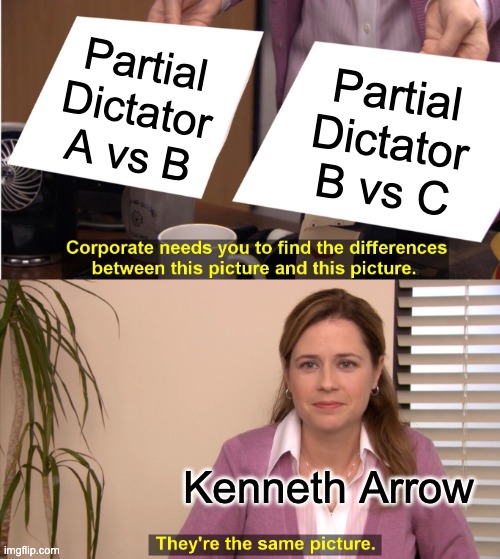

This post discusses an interesting illustration (based on Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem) of how difficult policy is. We consider a simple example of how even a single decision may not have an “optimal” solution. Not only is it impossible to “make everyone happy” (that’s obvious), but it’s not even possible to choose an option which isn’t blatantly wrong/unfair.

Let me know what you think (including corrections!) in the Disqus comments at the bottom of the page!

I stumbled across a twitter thread this morning about Hunter Biden’s laptop fiasco and it got me thinking about speech, media, and sociology. I’ve found myself increasingly interested in these types of topics the past half year or so, which, historically, is uncharacteristic of me. My current thoughts on the subject are that policy / politics is hard, and that delegation is wonderful, since I’d much rather have a trusted representative spend their full career thinking about these tough topics (representative democracy) rather than require every Tom, Dick, and Harry to have to give their best attempt at answering questions, but produce inevitably suboptimal results (pure democracy).

Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem states the following (my paraphrasing):

In a rank-order, single-winner election with 3 or more candidates, there exists no system which will always satisfy these (very reasonable!) criteria:

- Unanimity: If every voter prefers candidate A over candidate B, then candidate B should never win

- Independence of Irrelevant Alternatives (IIA): If A would beat B, then introducing a new (random) candidate C should never cause B to win

- Non-dictatorship: There is no “dictator”

Let’s break this down:

- Rank-order means that each voter ranks his/her order of preferences for candidates, e.g. A is better than C is better than B.

- Single-winner means that we seek a singular “best” candidate.

- Criteria:

- is pretty obvious. If one candidate is unanimously disliked, then they should never win.

- should be familiar to US citizens: a third candidate can often “split the vote” of a party, causing a majority-unfavored candidate to win. If you think about it, this makes no sense. Consider this analogy: if I like chocolate better than vanilla, then tasting strawberry for the first time should never make me suddenly like vanilla better than chocolate

- there should be no single person such that, with their vote alone, they can determine the outcome of the election

All of these criteria seem very reasonable! Yet, there exists no system which can always satisfy all 3! Another way of saying this is that there always exists some set of cast votes where it is impossible to choose a winner without violating one of these 3 criteria.

To illustrate how absurd this is, realize that the theorem is not saying that “no countries in the world reach all 3 criteria”, nor that “humans haven’t thought of a way to reach all 3 criteria”, this is saying that God himself could not devise a voting system that reaches all 3 criteria!

Furthermore, this is not just saying that “not everyone will be happy”, this is saying that it’s not mathematically possible to be “fair”!

Consider then an example of a single policy with 3 options: A, B, C (for example, (A) pave over marshland to construct vacation housing, (B) turn marshland into cropland, or (C) give marshland environmentally protected status). Even if you could collect accurate, rational votes from everyone, it’s still not guaranteed that you could decide on the “fair” winner!

Now multiply this by the countless policies being debated in the thousands of municipalities across the hundreds of countries in the world and the impossibility of the task of governance becomes incomprehensibly mind-boggling! From my background, it’s tempting to think that if only we had perfect data collection and infinite compute, that we could calculate the “optimal” solution, but in fact this may be not only un-computable, but flat-out impossible (even for God).

The proof goes roughly along the lines of constructing a set of votes such that, following the logic of criteria (1) and (2), you can derive that there must exist a “dictator” (by showing that there is a single person who, by changing their vote, can induce any candidate to win).

A little bit more specifically, the outline goes in 3 parts:

- We want to show that, among candidates A and B, there is a voter who can induce either one to win:

Consider a scenario where the left “half” of people prefer A over B and the right “half” prefer B over A. Then the person in the “middle” can tip the vote for either A or B. By criteria 2, adding candidate C cannot change whether A is preferred over B or vice-versa. - We want to show that, after adding candidate C, there is a voter who can induce either B or C to be preferred, regardless of everyone else’s preferences.

Consider the left “half” of people prefer A > B > C, while the right “half” prefer B > C > A, and the “middle” person prefers A > B > C. Then A should beat B, and since everyone prefers B > C, then B should beat C. Now imagine if every single person (except the “middle” person) switches the order of B and C such that C > B (i.e. C > B > A or A > C > B). Unless the “middle” person is a dictator, C should beat B, but we show that this is not the case.

Because we didn’t mess with A at all, A should still beat C. Now imagine the “middle” person switches his vote so that B > A: then B should win over A. But since A would win over C, then we can conclude (with a little more work) that B > A > C so the “middle” person caused B to beat C even though everyone else voted C above B. Finally, this result should hold regardless of how A is ranked in all the other voters by criteria 2. - It can be shown that the “middle” person in 1 and 2 are the same person, so that “middle” person is a dictator.

Policy is so hard that even trying to find a “fair” resolution to just 1 single issue (with 3 options and accurate rankings from every citizen) is mathematically impossible. Politics will always be messy and there’s no way around it.